Contrary to popular belief, the sailors of Columbus's day did not think they would sail right off the edge of the earth. They were, however, apprehensive about what they would find in their travels. Mistakes about marine life have ranged from inaccurate assumptions about the behavior of known species to fanciful depictions of animals that "might" exist.

Albrecht Dürer, Arion, 1514. According to the Greek legend, the gifted singer Arion was tossed overboard by sailors who wanted to steal his stuff. By the time he was thrown into the sea, however, he had bewitched a dolphin who came to his rescue. This dolphin sports more protuberances than any seen in nature, but in fairness to Dürer, who was known for his realism, the fact that he was illustrating a legend may have given him a greater sense of artistic license.

Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) was a Flemish cartographer and geographer, generally recognised as the creator of the first modern atlas.

Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1570.This excerpt of a map of Iceland shows sea monsters that many believed inhabited the surrounding waters.

Louis Figuier (1819-1894) was a French scientist and writer. He edited and published a yearbook from 1857 to 1894 — L'Année scientifique et industrielle — in which he compiled an inventory of the scientific discoveries of the year (it was continued after his death until 1914). He was the author of numerous successful works: Les Grandes inventions anciennes et modernes (1861), Le Savant du foyer (1862), La Terre avant le déluge (1863) illustrated by Édouard Riou, La Terre et les mers (1864), Les Merveilles de la science (1867-1891). The complete text with plates of La Terre avant le déluge is published electronically here. Some wonderful plates of his Les Mammifères are here.

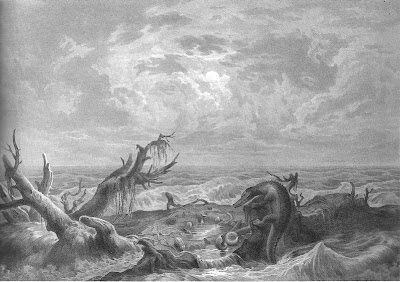

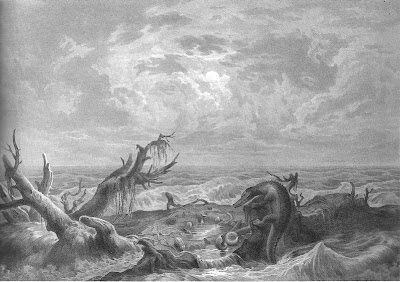

Louis Figuier, La Terre avant le Déluge, édition de 1864, Fig.130. L'ichthyosaure et le plésiosaure, illustration par Riou.

Franz Unger (1800-1870) was an Austrian botanist, paleontologist and plant physiologist. Unger was one of the major contributors to the field of paleontology, later turning to plant physiology and phytotomy. He hypothesized that (then unknown) combinations of simple elements inside a plant cell determine plant heredity and greatly influenced the experiments of his student Gregor Johann Mendel. Unger was a pioneer in documenting the relationships between soil and plants (1836).

Franz Unger, The Primitive World in Its Different Period of Formation, 1851

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint Fond (May 17, 1741–July 18, 1819) was a French geologist and traveller. By the late 18th century, Europe's savants had begun wrapping their brains around the concept of an ancient earth that had both predated humans by an unimaginable time span and crawled with strange creatures. The savants also hired capable artists and engravers to render accurate depictions of the fossils they found. The year 1780 marked the discovery of an enormous fossil reptile in underground quarries near the Dutch town of Maastricht. Nineteen years later, Faujas published a description of the reptile. The illustration of the fossil itself is pretty accurate (the oval-shaped objects with the skull are fossil sea urchins). Faujas's interpretation wasn't quite as accurate as the pictures. He classified it as a giant crocodile. Today, the fossil is identified as a mosasaur, an extinct marine reptile.

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint Fond, Montagne de Saint-Pierre, 1799

Gaspar Schott (1608-1666) was a German scientist, specializing in the fields of physics, mathematics and natural philosophy. Schott was a one-time student and long-time collaborator of the German Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher. Besides editing and defending Kircher's works, Schott published some of his own. This page from the second volume of his Physica Curiosa shows a motley assortment of sea monsters, including a fish resembling a monk (upper left), a marine monster looking suspiciously like a bishop (lower right), and two chimerical creatures with long, fishy tails. Similar depictions appeared in numerous works in the 16th and 17th centuries. Religious tensions of the time might have contributed to the strong resemblance between alleged monsters and clerical figures.

Caspar Schott, Physica Curiosa, 1662

Konrad Gessner (1516-1565) was a Swiss naturalist and bibliographer. His five-volume Historiae animalium (1551-1558) is considered the beginning of modern zoology. His great zoological work, Historiae animalium, appeared in 4 vols. (quadrupeds, birds, fishes) folio, 1551-1558, at Zürich, a fifth (snakes) being issued in 1587: This work is the starting-point of modern zoology. Not content with such vast works, Gessner put forth in 1555 his book entitled Mithridates de differentis linguis, an account of about 130 known languages.

Conrad Gesner, Icones Animalium, 1560. Gesner was one of the finest naturalists of the 16th century, but he occasionally misfired. In this woodcut, a mother whale and her young look awfully porcine.

Pierre Pomet (1658-1699) was a French pharmacist. After travels in Italy, Germany, Great Britain and Holland he returned to Paris where he opened pharmacy. He acquired a great reputation quickly. He gave courses to explain the manufacture of his products. He regularly published a catalog of drugs made up of his vast collection as well as a Cabinet of curiosities. In 1694 he published the General History of drugs, plants animals and minerals, illustrated with more than 400 figures.

Histoire Générale des Drogues, 1694. Pomet pictured both a sea unicorn (top) and a narwhal (bottom). Unlike the first creature, the second was real, and its horn was often mistaken — or deliberately passed off — as a unicorn horn, believed capable of curing all kinds of diseases and poisonings. As Europe's upper-crust families showed such a fondness for poisoning their own, such antidotes were always in demand. Not long after Pomet's book was published, the narwhal was identified as a "false unicorn."

Albertus Seba by Jacobus Houbraken (1731)

Albertus Seba (1665-1736) was a Dutch pharmacist, zoologist and collector. Born in East-Frisia, Seba moved to Amsterdam as an apprentice and opened around 1700 a pharmacy near the harbour. Seba asked sailors and ship surgeons to bring exotic plants and animal products he could use for preparing drugs. Seba also started to collect snakes, birds, insects, shells and lizards in his house. From 1711 he delivered drugs to the Russian court in Saint Petersburg and sometimes accepted fresh ginger as payment. Seba promoted his collection with the head-physician to the czar, Robert Arskine, and early 1716 Peter the Great bought the complete collection. In 1728 Seba had become a member of the Royal Society. In 1735 Linnaeus visited him twice. In 1734 Seba had published a Thesaurus of animal specimens with beautiful engravings. The full name of the Thesaurus is, with a dual Latin–Dutch title, Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio — Naaukeurige beschryving van het schatryke kabinet der voornaamste seldzaamheden der natuur (Accurate description of the very rich thesaurus of the principal and rarest natural objects). The last two of the four volumes were published after his death (1759 and 1765). Today, the original 446-plate volume is on permanent exhibit at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague, Netherlands. Recently, a complete example of the Thesaurus sold for US $460,000 at an auction. In 2001, Taschen Books published a reprint of the Thesaurus.

Albertus Seba, Thesaurus, 1734. Seba portrayed this hydra in the 18th century. Seba had his doubts about its authenticity, but more than one "respectable eye witness" vouched for the accuracy of the stuffed specimen, so he published this picture of it. Seba's mistake is understandable in light of the fact that most genuine animals were either preserved in spirits or stuffed by the time they reached him.

Athanasius Kircher, the 17th-century German Jesuit polymath established a fabulous museum in Rome, filled with antiquities, speaking tubes, odd animals and fossils. Some of these "wonders" were too fantastic to be true. (Kircher believed every story he ever heard about someone catching a dragon — assuming that someone was a pope.) But much of what he collected was absolutely real. These fish carcasses and shark teeth must have looked outlandish to the visitors to Kircher's museum, but fish like these swim in the sea today. After Kircher died, Buonanni took over his collection and published a catalog in the early 18th century. These images from the catalog show some 18th-century progress in accurately depicting sea life. Numerous works by Kircher were published electronically by Max Planck Gesellschaft here.

Ath. Kircher and Filippo Buonanni,

Musæum Kircherianum,1709

Nicolas Steno (Danish: Niels Stensen; latinized to Nicolaus Stenonis) (1638 -1686) was a pioneer in both anatomy and geology. Already in 1659 he decided not to accept anything simply written in a book, instead resolving to do research himself. He is considered the father of geology and stratigraphy.

Niels Stensen, Canis Carchariae Dissectum Caput, 1667. Strange as it looks by today's standards, this picture of a dissected head of a giant white shark actually marked significant progress in marine biology. For years, fossilized shark teeth were believed to be tongues of serpents turned to stone by St. Paul, and hence were named glossopetrae, or "tongue stones." Niels Stensen correctly identified tongue stones as shark teeth.

Pierre Dénys de Montfort (1766 – 1820) was a French naturalist, in particular a malacologist, remembered today for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of the giant squid Architeuthis, which was thought to be an old wives' tale, and for which he was long dismissed. He was inspired by a description from 1783 of an eight-metre long tentacle found in the mouth of a sperm whale. Dénys de Montfort was author of Conchyliologie systématique, et classification méthodique de coquilles (2 vols., Paris 1808 - 1810) and of Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques (2 vols., Paris 1801 - 1802) published as an addendum to the comte de Buffon's Histoire naturelle générale et particulière.

Denys de Montfort bragged that if this representation were swallowed, he would next represent a cephalopod embracing the Straits of Gibraltar. Seventy years later, Alexander Winchell did two admirable things: He called Denys de Montfort's depiction a sailor's yarn, but also suggested, "the unexplored depths of the ocean conceal the forms of octopods that far surpass in magnitude any of the species known to science." Winchell was right on both counts.

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carolus Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history studies. He is usually referred to, especially in older literature, as Aldrovandus. The Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum has published some of his works:

Ulisse Aldrovandi, De Piscibus, 1613. Aldrovandi sometimes combined impressive realism (a recognizable shark) with puzzling chimera. The fish on the bottom has a mammal-like face with a saw protruding from the head, dragon-like scales, fishy fins and flippers. Aldrovandi sometimes exhibited what the 18th-century naturalist Buffon would later describe as "a tendency towards credulity." Of the stingray, Aldrovandi observed, "They love music, the dance and witty remarks." Exactly how stingrays exhibited their affection for these niceties is unknown.

Honorius Philoponus, Novi Orbis Indiae Occidentalis, 1621. The whale-as-island made another appearance in this 17th-century engraving. It shows the whale, Jasconius, in an account of the voyage of Saint Brendan. Some of the monks were preoccupied with mass when the nature of the island became obvious.

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint Fond (May 17, 1741–July 18, 1819) was a French geologist and traveller. By the late 18th century, Europe's savants had begun wrapping their brains around the concept of an ancient earth that had both predated humans by an unimaginable time span and crawled with strange creatures. The savants also hired capable artists and engravers to render accurate depictions of the fossils they found. The year 1780 marked the discovery of an enormous fossil reptile in underground quarries near the Dutch town of Maastricht. Nineteen years later, Faujas published a description of the reptile. The illustration of the fossil itself is pretty accurate (the oval-shaped objects with the skull are fossil sea urchins). Faujas's interpretation wasn't quite as accurate as the pictures. He classified it as a giant crocodile. Today, the fossil is identified as a mosasaur, an extinct marine reptile.

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint Fond, Montagne de Saint-Pierre, 1799

Gaspar Schott (1608-1666) was a German scientist, specializing in the fields of physics, mathematics and natural philosophy. Schott was a one-time student and long-time collaborator of the German Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher. Besides editing and defending Kircher's works, Schott published some of his own. This page from the second volume of his Physica Curiosa shows a motley assortment of sea monsters, including a fish resembling a monk (upper left), a marine monster looking suspiciously like a bishop (lower right), and two chimerical creatures with long, fishy tails. Similar depictions appeared in numerous works in the 16th and 17th centuries. Religious tensions of the time might have contributed to the strong resemblance between alleged monsters and clerical figures.

Caspar Schott, Physica Curiosa, 1662

Konrad Gessner (1516-1565) was a Swiss naturalist and bibliographer. His five-volume Historiae animalium (1551-1558) is considered the beginning of modern zoology. His great zoological work, Historiae animalium, appeared in 4 vols. (quadrupeds, birds, fishes) folio, 1551-1558, at Zürich, a fifth (snakes) being issued in 1587: This work is the starting-point of modern zoology. Not content with such vast works, Gessner put forth in 1555 his book entitled Mithridates de differentis linguis, an account of about 130 known languages.

Conrad Gesner, Icones Animalium, 1560. Gesner was one of the finest naturalists of the 16th century, but he occasionally misfired. In this woodcut, a mother whale and her young look awfully porcine.

Pierre Pomet (1658-1699) was a French pharmacist. After travels in Italy, Germany, Great Britain and Holland he returned to Paris where he opened pharmacy. He acquired a great reputation quickly. He gave courses to explain the manufacture of his products. He regularly published a catalog of drugs made up of his vast collection as well as a Cabinet of curiosities. In 1694 he published the General History of drugs, plants animals and minerals, illustrated with more than 400 figures.

Histoire Générale des Drogues, 1694. Pomet pictured both a sea unicorn (top) and a narwhal (bottom). Unlike the first creature, the second was real, and its horn was often mistaken — or deliberately passed off — as a unicorn horn, believed capable of curing all kinds of diseases and poisonings. As Europe's upper-crust families showed such a fondness for poisoning their own, such antidotes were always in demand. Not long after Pomet's book was published, the narwhal was identified as a "false unicorn."

Albertus Seba by Jacobus Houbraken (1731)

Albertus Seba (1665-1736) was a Dutch pharmacist, zoologist and collector. Born in East-Frisia, Seba moved to Amsterdam as an apprentice and opened around 1700 a pharmacy near the harbour. Seba asked sailors and ship surgeons to bring exotic plants and animal products he could use for preparing drugs. Seba also started to collect snakes, birds, insects, shells and lizards in his house. From 1711 he delivered drugs to the Russian court in Saint Petersburg and sometimes accepted fresh ginger as payment. Seba promoted his collection with the head-physician to the czar, Robert Arskine, and early 1716 Peter the Great bought the complete collection. In 1728 Seba had become a member of the Royal Society. In 1735 Linnaeus visited him twice. In 1734 Seba had published a Thesaurus of animal specimens with beautiful engravings. The full name of the Thesaurus is, with a dual Latin–Dutch title, Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio — Naaukeurige beschryving van het schatryke kabinet der voornaamste seldzaamheden der natuur (Accurate description of the very rich thesaurus of the principal and rarest natural objects). The last two of the four volumes were published after his death (1759 and 1765). Today, the original 446-plate volume is on permanent exhibit at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague, Netherlands. Recently, a complete example of the Thesaurus sold for US $460,000 at an auction. In 2001, Taschen Books published a reprint of the Thesaurus.

Albertus Seba, Thesaurus, 1734. Seba portrayed this hydra in the 18th century. Seba had his doubts about its authenticity, but more than one "respectable eye witness" vouched for the accuracy of the stuffed specimen, so he published this picture of it. Seba's mistake is understandable in light of the fact that most genuine animals were either preserved in spirits or stuffed by the time they reached him.

Athanasius Kircher, the 17th-century German Jesuit polymath established a fabulous museum in Rome, filled with antiquities, speaking tubes, odd animals and fossils. Some of these "wonders" were too fantastic to be true. (Kircher believed every story he ever heard about someone catching a dragon — assuming that someone was a pope.) But much of what he collected was absolutely real. These fish carcasses and shark teeth must have looked outlandish to the visitors to Kircher's museum, but fish like these swim in the sea today. After Kircher died, Buonanni took over his collection and published a catalog in the early 18th century. These images from the catalog show some 18th-century progress in accurately depicting sea life. Numerous works by Kircher were published electronically by Max Planck Gesellschaft here.

Ath. Kircher and Filippo Buonanni,

Musæum Kircherianum,1709

Nicolas Steno (Danish: Niels Stensen; latinized to Nicolaus Stenonis) (1638 -1686) was a pioneer in both anatomy and geology. Already in 1659 he decided not to accept anything simply written in a book, instead resolving to do research himself. He is considered the father of geology and stratigraphy.

Niels Stensen, Canis Carchariae Dissectum Caput, 1667. Strange as it looks by today's standards, this picture of a dissected head of a giant white shark actually marked significant progress in marine biology. For years, fossilized shark teeth were believed to be tongues of serpents turned to stone by St. Paul, and hence were named glossopetrae, or "tongue stones." Niels Stensen correctly identified tongue stones as shark teeth.

Pierre Dénys de Montfort (1766 – 1820) was a French naturalist, in particular a malacologist, remembered today for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of the giant squid Architeuthis, which was thought to be an old wives' tale, and for which he was long dismissed. He was inspired by a description from 1783 of an eight-metre long tentacle found in the mouth of a sperm whale. Dénys de Montfort was author of Conchyliologie systématique, et classification méthodique de coquilles (2 vols., Paris 1808 - 1810) and of Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques (2 vols., Paris 1801 - 1802) published as an addendum to the comte de Buffon's Histoire naturelle générale et particulière.

Denys de Montfort bragged that if this representation were swallowed, he would next represent a cephalopod embracing the Straits of Gibraltar. Seventy years later, Alexander Winchell did two admirable things: He called Denys de Montfort's depiction a sailor's yarn, but also suggested, "the unexplored depths of the ocean conceal the forms of octopods that far surpass in magnitude any of the species known to science." Winchell was right on both counts.

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carolus Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history studies. He is usually referred to, especially in older literature, as Aldrovandus. The Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum has published some of his works:

- Ornithologiae, hoc est de avibus historia libri XII (1599) Digitized version of 1637 edition

- De animalibus insectis libri septem, cum singulorum iconibus ad vivum expressis (1602) Digitized version of 1637 edition

- Ornithologiae tomus alter (1600) Digitized version

Ulisse Aldrovandi, De Piscibus, 1613. Aldrovandi sometimes combined impressive realism (a recognizable shark) with puzzling chimera. The fish on the bottom has a mammal-like face with a saw protruding from the head, dragon-like scales, fishy fins and flippers. Aldrovandi sometimes exhibited what the 18th-century naturalist Buffon would later describe as "a tendency towards credulity." Of the stingray, Aldrovandi observed, "They love music, the dance and witty remarks." Exactly how stingrays exhibited their affection for these niceties is unknown.

Honorius Philoponus, Novi Orbis Indiae Occidentalis, 1621. The whale-as-island made another appearance in this 17th-century engraving. It shows the whale, Jasconius, in an account of the voyage of Saint Brendan. Some of the monks were preoccupied with mass when the nature of the island became obvious.

I went to Loch Ness when I was a child. I didn't see anything but I really thought there was something moving around under the water. Who knows? I'm pretty imaginative. I think these guys were too though there is indeed a giant squid and I've heard there are enormous roaches at the bottom of the ocean.

ReplyDeleteGreat collection, and we could add Hugo's "Roi des auxcriniers"

ReplyDeletehttp://expositions.bnf.fr/hugo/grands/250.htm

It's here:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.facebook.com/album.php?aid=2015295&id=1531531752#/photo.php?pid=30227139&id=1531531752

this is wonderful G ... there are still so many secrets hidden in the oceans ... a parallel universe right below our blinkered vision ...

ReplyDeleteI always wanted to be a mermaid when I grew up ... and what about the Lorelei ...

'fact' and fiction are often just two perspectives of the same sight ...