Yakov Georgievich Chernikhov (1889 - 1951) was a constructivist architect and graphic designer. His books on architectural design published in Leningrad between 1927 and 1933 are amongst the most innovatory texts (and illustrations) of their time. Chernikov was born to a poor family, one of 11 children. After studying at the college of art in Odessa, he moved in 1914 to Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and joined the Architecture faculty of the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1916, where he later studied under Leon Benois.

In 1927 he organized in Leningrad his own Science and Research Pilot Laboratory for Architectural Shapes and Graphical Studies, where with a group of students and assistants he became actively involved, in experimental and design work.

Chernikhov with some of his students

Chernikhov with some of his students

Greatly interested in futurist movements, including constructivism, and the suprematism of Malevich (with whom he was acquainted), he set out his ideas in a series of books in the late 1920s and early 1930s, including:

- The Art of Graphic Representation (1927)

- Fundamentals of Contemporary Architecture (1930)

- The Construction of Architectural and Machine Forms (1931)

- Architectural Fantasies (1933)

The latter, a very fine example of colour printing, was perhaps the last avant-garde art book to be published in Russia during the Stalinist era. Its remarkable designs uncannily predict the architecture of the later 20th century. However his unusual ideas meant that Chernikhov was distrusted by the regime.

The latter, a very fine example of colour printing, was perhaps the last avant-garde art book to be published in Russia during the Stalinist era. Its remarkable designs uncannily predict the architecture of the later 20th century. However his unusual ideas meant that Chernikhov was distrusted by the regime.

Although he continued work as a teacher and held a number of one-man shows, few of his designs were built and very few appear to have survived. Amongst the latter is the tower of the Red Carnation factory in St. Petersburg, here shown on the left (2006).

In various years he also executed a series of works in the area of architectural theory, proportions, architectural aesthetics, and the methodology of teaching the graphical disciplines. Chernikhov also produced a number of richly designed architectural fantasies of historic architecture, which were never exhibited in his lifetime.

1. "Fundamentals of Modern Architecture" (1925-30)In 1930 Iakov Chernikhov published his first major book in the field of architecture, "Fundamentals of Modern Architecture", where he reinterpreted the fundamental concepts of architecture, such as space, harmony, statics, functionality, construction, and composition proceeding from an earlier proposed postulates concerning a basic shift of rhythms in favor of a rhythm of proportions and the predominance of asymmetry.

“By rejecting naked, ascetic, "boxed" architecture, which offers no architectural saturation of space and does not satisfy our eye from the aesthetic side or the side of emotional experience, I tried through consonance of basic masses to achieve a truly expressive architectural image in new forms.”

“By rejecting naked, ascetic, "boxed" architecture, which offers no architectural saturation of space and does not satisfy our eye from the aesthetic side or the side of emotional experience, I tried through consonance of basic masses to achieve a truly expressive architectural image in new forms.” “The architect should not limit the sphere of his work with narrow frames and servile imitations, but, where necessary, should overcome obstacles by means of his powerful fantasy and bravely move forward. Those who think that the architect’s activity should embrace only current realistic requirements are thinking incorrectly and falsely."

“The architect should not limit the sphere of his work with narrow frames and servile imitations, but, where necessary, should overcome obstacles by means of his powerful fantasy and bravely move forward. Those who think that the architect’s activity should embrace only current realistic requirements are thinking incorrectly and falsely."

2. "Architectural Fantasies

2. "Architectural Fantasies"

(1925-33)

Architectural Fantasies: 101 compositions in color and 101 in black-and-white—is the last and, probably, the best book published during Chernikhov’s life and summarizing his search for the forms and images of new architecture. In the second half of the 20th century this book, in which Chernikhov’s compositional talent appeared with greatest brilliance, became mandatory for architects in Japan, Europe, and the United States.

"An epoch of the greatest reconstructions of human relations must be reflected by its own unforgettable highly artistic monuments. It will create its own style not by rephrasing the old basics, but through creative quests for new forms with new content under the new requirements.”

"An epoch of the greatest reconstructions of human relations must be reflected by its own unforgettable highly artistic monuments. It will create its own style not by rephrasing the old basics, but through creative quests for new forms with new content under the new requirements.”  3. "Construction of Architectural and Machine Forms" (1925-1931)

3. "Construction of Architectural and Machine Forms" (1925-1931) Having graduated in 1925 from the Academy of Arts, Iakov Chernikhov became fascinated with industrial architecture, which was the area of construction showing the most progress. In comparison with other areas, it possessed multifunctionality and a wider elite, and consequently promised a wider field of activity in terms of form creation.

Having graduated in 1925 from the Academy of Arts, Iakov Chernikhov became fascinated with industrial architecture, which was the area of construction showing the most progress. In comparison with other areas, it possessed multifunctionality and a wider elite, and consequently promised a wider field of activity in terms of form creation.  The pathos of industrialization, with its sublime, heroic-romantic aura in those years, defined creative quests in various forms of art. 1927 witnessed the debut of Alexander Mosolov’s one-part symphonic piece, The Factory, in which the image of a working factory was reproduced by musical means. It immediately entered the repertoire of the leading orchestras, and for several years its performance opened concerts of symphonic music in Moscow and Leningrad. Also at that time Sergey Prokofiev wrote his famous Le Pas d'acier, and Dmitry Shostakovich composed the ballet Bolt. Alexander Mosolov : Steel - The Iron Foundry

The pathos of industrialization, with its sublime, heroic-romantic aura in those years, defined creative quests in various forms of art. 1927 witnessed the debut of Alexander Mosolov’s one-part symphonic piece, The Factory, in which the image of a working factory was reproduced by musical means. It immediately entered the repertoire of the leading orchestras, and for several years its performance opened concerts of symphonic music in Moscow and Leningrad. Also at that time Sergey Prokofiev wrote his famous Le Pas d'acier, and Dmitry Shostakovich composed the ballet Bolt. Alexander Mosolov : Steel - The Iron Foundry

Soviet Union 1920s: Concert of Factory Sirens and Steam Whistles. The conductor stands on the roof of the tallest house and conducts by means of flags. Source: katardat.org, The Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia 1920-1929.

Soviet Union 1920s: Concert of Factory Sirens and Steam Whistles. The conductor stands on the roof of the tallest house and conducts by means of flags. Source: katardat.org, The Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia 1920-1929.

"Black chimneys, buildings, crankshafts, cylinders. Ready to talk to you, I raise my hands, I sing of you, my iron friends. I go to the factory as to a festival, as to a feast." Thus wrote Alexander Gastayev in his Poetics of a Work Offensive, a distinctive manifesto of proletarian poetry in those years.

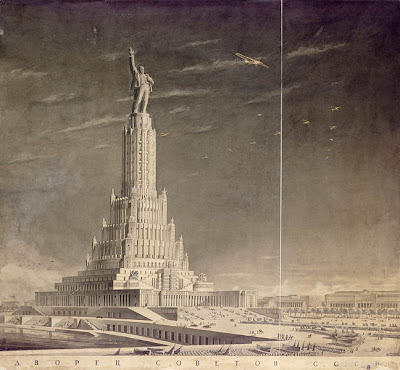

4. "Palaces of Communism" (1934-1941)In the mid-1930s, after the establishment of Constructivism and the proclamation of a principally new approach to architectural ideology in Soviet Russia, Iakov Chernikhov, like many others, was subject to a vicious criticism. His books were withdrawn from libraries, and those already submitted to the printer were never published.

N

evertheless, Chernikhov preserved his ability to generate new ideas. By now already clearly in the Piranesi style, he created in 1934-1946 a cycle of works that included: The Architecture of Palaces, The Architectural Ensembles, The Architecture of the Future, The Architecture of Bridges, and The Palaces of Communism in which the author not only studies the image of the architecture of the new epoch, but also the issues of formation of the architectural ensemble.

5. "Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War" (1942 -1945) In 1942, when the Union of Architects announced a competition for monuments to war heroes, Chernikhov created the design-graphic suite “Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War” that embodied the tragedy and greatness of Russia in the Second World War. For the competition Chernikhov prepared nine Pantheon project-perspectives, made in large format (900x1200 mm), which was unusual for the author. He has worked out the detailed program for the Pantheon conceived as a grandiose museum. After the War the total number exceeded 50.

In 1942, when the Union of Architects announced a competition for monuments to war heroes, Chernikhov created the design-graphic suite “Pantheons of the Great Patriotic War” that embodied the tragedy and greatness of Russia in the Second World War. For the competition Chernikhov prepared nine Pantheon project-perspectives, made in large format (900x1200 mm), which was unusual for the author. He has worked out the detailed program for the Pantheon conceived as a grandiose museum. After the War the total number exceeded 50. 6. Some Influences

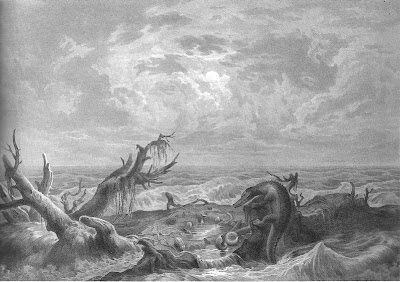

6. Some Influences Étienne-Louis Boullée, Projet de cénotaphe à Newton, vue en élévation, 1784.

Étienne-Louis Boullée, Projet de cénotaphe à Newton, vue en élévation, 1784. Erich Mendelsohn, Einstein Tower in Potsdam, 1920s

Erich Mendelsohn, Einstein Tower in Potsdam, 1920s Tatlin’s Tower or The Monument to the Third International, 1920s (not realized)

Tatlin’s Tower or The Monument to the Third International, 1920s (not realized).

El Lissitzky, Der Wolkenbügel (The Cloud Iron), 1925 (not realized) 7. Sources

El Lissitzky, Der Wolkenbügel (The Cloud Iron), 1925 (not realized) 7. Sources

Constructivist architecture (Wikipedia)

Yakov Chernikhov International Foundation (with many more images)